Das SDG 2: Food Security

Hunger is the unfulfilled desire for food, a feeling that arises when one does not have what is necessary to adequately nourish oneself. The term hunger describes both the sensation and the condition of malnutrition or undernutrition. It encompasses physical, social, socio-political, psychological, and economic aspects. To end hunger worldwide, as formulated in SDG 2, it is necessary to ensure regular, healthy, and sufficient nutrition – for everyone.

The right to adequate food is one of the fundamental human rights!

Hunger and food insecurity – facts and figures

While the number of hungry people worldwide initially declined after the turn of the millennium, the curve has risen sharply again since 2015 and especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, reaching in 2023 a level comparable to almost 20 years ago. According to various estimates, between 735 and 828 million people—just under 10% of the world’s population – currently suffer from chronic hunger (Global Hunger Index). This means: about one in ten people on Earth is hungry!

Around 2.4 billion people—and thus a good 30% of the world’s population—are affected by moderate to severe food insecurity. They not only suffer constant hunger, but due to inadequate and unbalanced diets also experience a persistent lack of essential nutrients such as iron, iodine, zinc, or vitamins.

The consequences of this “hidden hunger” are not necessarily visible at first glance. In the long term, however, nutrient deficiencies lead to serious diseases and an increased risk of death. It harms not only the individual but can hinder the entire (sustainable) development and economy of the affected regions. Those affected become ill more quickly, are weakened over time due to lack of food, and are limited in their physical and mental performance abilities. Three quarters of all hungry people live in rural areas.

According to the Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2023, the hotspots of hunger are in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. According to the report, the hunger situation is particularly severe in the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lesotho, Madagascar, Niger, Haiti, and Yemen, although for some countries there is not always sufficient data to calculate the GHI. The nutritional situation in Burundi, Somalia, Burkina Faso, South Sudan, and Pakistan is also classified as very serious.

“More than a quarter of a billion people are on the brink of starvation,” states the Global Report on Food Crisis (May 2022). And the situation has not improved since then…

Food insecurity is also widespread in major economies: in 2022, around 16.5 million chronically undernourished people lived in the so-called “wealthy” countries (FIAN). In the United Kingdom, for example, 10% of women and 9% of men reported experiencing food insecurity. In Germany, an estimated 1.5 million people also eat in a one-sided and insufficient manner. Most often, it is elderly, ill, and people living alone who are inadequately nourished, but many children are also affected by nutrient deficiencies in their diets. Especially in poorer families, cheap, energy-dense foods such as refined flour products, sweets, and fast food are consumed. This leads to obesity and a lack of essential nutrients. Sixty percent of adults in Germany are overweight and therefore more susceptible to cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and other illnesses (UN Hunger Report, July 2023).

Particularly affected: women and children

In most countries, women report food insecurity more often than men. Due to limited access to land, money or credit, markets, education, and technology, as well as unequal power relations within households, women often have little (or less) control over the proceeds of their labor—whether food or cash. Worldwide, nearly one third of employed women work in agriculture, not counting the self-employed and unpaid family workers. At the same time, women and girls prepare most meals globally and play a crucial role in food production, processing, and distribution.

In times of crisis or rising food prices, women and girls are often the first to eat less or poorer-quality food—even though they frequently spend more time and energy ensuring their family’s nutrition. For pregnant and breastfeeding women, inadequate and poor nutrition poses an additional risk and endangers the lives of the unborn.

Infants and children are particularly affected by hunger and malnutrition. Malnutrition restricts their physical growth and cognitive development. They learn less and have greater difficulty concentrating. Hunger prevents children from attending school and acquiring the knowledge necessary to later earn a living through self-determined work.

Every thirteen seconds, a child dies because it does not have enough to eat!

“World agriculture could easily feed 12 billion people. This means that a child who dies of hunger today is being murdered.”

(Jean Ziegler, former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food)

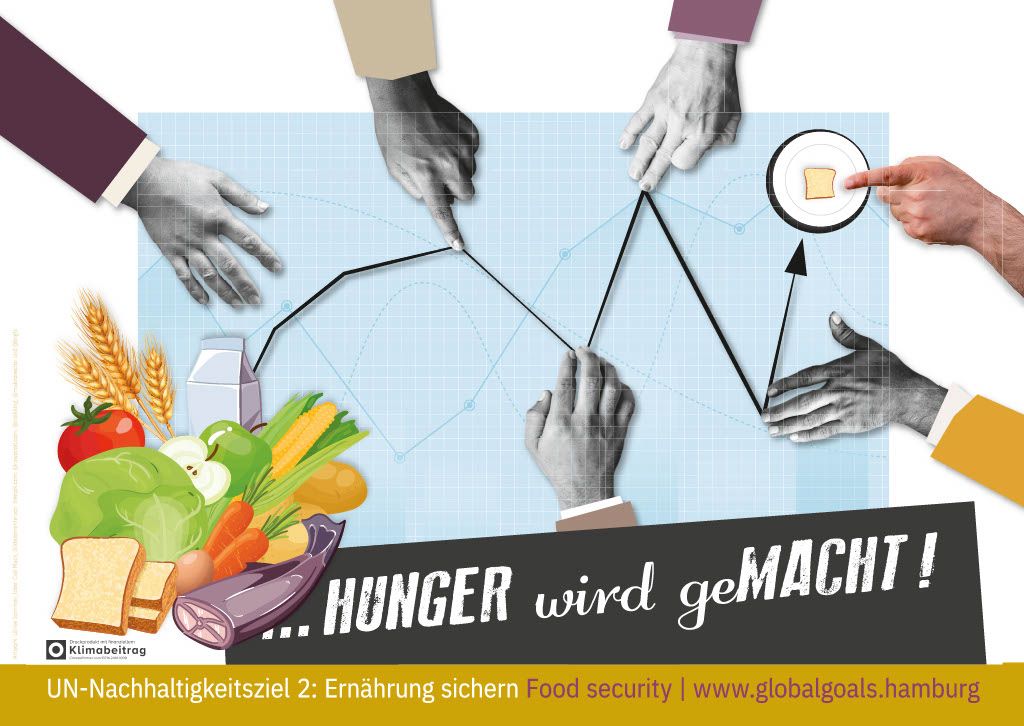

Hunger is man-made: causes and structural–systemic conditions

While some countries have been experiencing hunger crises for decades—often with little attention from the public—the topic has recently returned more strongly to public awareness due to current wars (Ukraine, Nagorno-Karabakh, Gaza Strip). Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has, among other things, brought grain production and exports from the Black Sea region, the “breadbasket of the world,” almost to a standstill. At the same time, the deliberate withdrawal of food is being used as a weapon to coerce war objectives: food transports are blocked, supply chains disrupted, agricultural cultivation prevented, and people starved.

Increasingly, the media also report on the growing and tangible effects of advancing climate change—such as droughts, heat waves, floods, unpredictable rainfall, strong temperature fluctuations, and other extreme weather events—and their impact on food production (crop failures, destroyed grazing and cultivation areas, lack of animal feed). As a result, the food crisis is once again moving more prominently into public consciousness.

Since 2020, the number of undernourished and hungry people worldwide has surged due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The reasons include shortages in food supply, loss of income, rising prices, and increasing social and economic inequality.

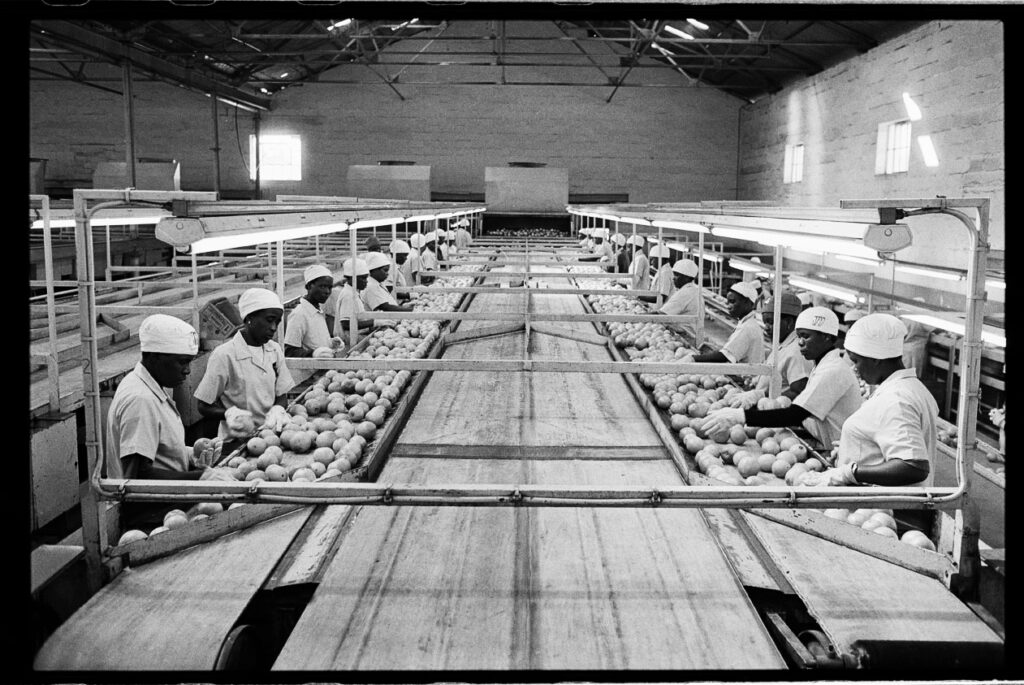

Photo: William Matlala

Purely in mathematical terms, every person in the world today would have 30% more to eat than 50 years ago. According to experts, there is enough wholesome food for 10 to 12 billion people—or it could be produced. The problem therefore does not lie in insufficient food production but in the quality and unequal distribution of food. “More of the same is not enough…,” says Dirk Meyer of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). What is needed instead is a fundamental transformation of agricultural and food systems—away from a system focused purely on quantitative food production. The intensification of agriculture, driven in part by high agricultural subsidies, results in significant ecological problems (nutrient surpluses, water pollution, pesticide use and insect die-off, biodiversity loss, and inadequate animal welfare). What is required is a shift in thinking and a restructuring of agricultural policy—toward a system oriented toward the common good, promoting biodiversity and a circular economy, and guided by criteria of ecological sustainability and social justice.

To achieve this, the discriminatory and primarily profit-oriented structures of the capitalist global agricultural market must be changed. Hunger is, to a great extent, a consequence of exclusion and discrimination, of political decisions against certain population groups, of agricultural and trade policies, distribution struggles, and speculation. Millions of people go hungry because they are discriminated against socially, politically, economically, and geographically and are excluded from adequate supply. Half of all hungry people are smallholder farmers, landless people (seasonal workers, tenants), as well as Indigenous peoples, nomads, and fishers. They have little influence on political decisions, are marginalized in everyday life, economically disadvantaged, and pushed into areas where survival is particularly difficult: from city centers into slums, and from fertile farmland into arid regions and areas without sufficient access to water or infrastructure (FIAN).

While the global cultivation area for palm oil, animal feed, biofuels, and renewable raw materials has continuously increased since 2000, the area used to grow staple foods such as potatoes, millet, rye, and sorghum has decreased by 24 million hectares during the same period: “Global agriculture is increasingly less geared toward feeding people.” (Roman Herre, FIAN)

Alongside wars and conflicts, pandemics, natural disasters, and climate change, growing inequalities and market disruptions, land grabbing and displacement, food speculation, and rising food prices continue to fuel food and hunger crises.

Speculation in agricultural commodities—often staple foods such as maize and wheat—is partly responsible for the sharp price increases of recent years and thus contributes to global food crises. Financial advisers promote agricultural commodities as investments promising high returns. By betting on the price development of staple foods, investment banks and funds drive prices upward. Rising food prices mean less food for poor population groups and often trigger hunger crises (foodwatch).

“Hunger kills roughly 100,000 people worldwide every day. Hardly anyone speaks about this genocide, let alone about remedies. Against this backdrop, and in view of the unrestrained neoliberalism of the financial markets, the talk of the powerful about Christian values, solidarity, and justice reveals itself as pure hypocrisy.” (Jean Ziegler)

For more on the global food crisis, see also here.

Further information can be found at the World Food Programme, Welthungerhilfe, FIAN, in the Kritischer Agrarbericht 2023, or in the international project FoodUnfolded.

see also: Goal 2 – Fast facts

UN Sustainable Development Goal 2 aims to

end hunger worldwide, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture.

Its subtargets include: ensuring access for all people to safe and nutritious food; ending all forms of malnutrition; doubling the productivity and incomes of small-scale farmers; promoting sustainable food production and resilient agricultural practices; and preserving genetic diversity in food production.

This is to be achieved through investments in rural infrastructure, agricultural research, technology and gene banks; through preventing agricultural trade restrictions, market distortions, and export subsidies; and through ensuring stable food commodity markets and access to information for all stakeholders.

However, the current UN Hunger Report makes it clear that the world is not on track to achieve these goals and end hunger by 2030. Instead, it is expected that 600–800 million people will still suffer from chronic hunger by then (UN Report on Food Security in the World 2022).

Possible solutions

To prevent this, a cross-sector effort is needed involving politics, the agricultural sector, farmers’ associations, and civil society—and with the participation of all countries—to initiate a fundamental systemic transformation in agricultural, trade, and economic policy:

towards healthy, sufficient, and nutrient-rich food accessible to all; towards fair and inclusive value chains; towards strengthening the resilience of producer countries in times of disruptions and crises (wars, natural disasters, pandemics); and towards greater climate justice.

This global task is enormous and encounters considerable resistance—for example, from local farmers who fear or already experience significant losses due to the reduction of agricultural subsidies. But there are also farming enterprises here that advocate for new thinking and different agricultural policies and that lead by example.

A variety of global, national, and regional alliances are working for a transformation of food and agricultural systems.

The United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), as the largest humanitarian organization in the world, has been dedicated to fighting global hunger since its founding in 1963 and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2020 for its efforts. On an international governmental level, the Alliance for Global Food Security, founded in May 2022 within the G7 framework, aims to establish multilateral financing structures to support less financially strong countries with immediate measures against current hunger and food crises.

There are also numerous non-profit organizations, initiatives, and campaigns advocating for a fundamental agroecological transformation of global agriculture as well as a sustainable and solidarity-based redesign of food systems. Their goals include, among others:

- Less grain in animal feed and car tanks

- Reduced use of pesticides

- Reduced production and consumption of animal products

- Less food waste

- Fewer imports of exotic agricultural products…

Everyone can contribute: buy only as much food as you need, eat seasonal, organically produced, fresh, and locally grown products, reduce the consumption of meat, fish, and other animal products, and share any surplus food with others. In doing so, you help strengthen food systems and reduce emissions. Through shared responsible action and consumption, ecological and solidarity-based agriculture, permaculture and circular economy, urban gardening and urban self-sufficiency, and the use of rescued food can be tested and promoted (as, for example, in the Hamburg project Minitopia).

Get Involved with initiatives and organizations working for a sustainable transformation of food and agricultural systems.

Rescue and Share Food

- foodsharing.de: an international movement advocating mindful use of resources and sustainable food systems

- Zu gut für die Tonne: an initiative to share leftover food and stop food waste

- Too Good to Go: an app to rescue unsold food from shops and restaurants

Campaigns

- Wir haben es satt!: Alliance for an alternative agricultural policy

- Slow Food Movement: promotes socially and ecologically responsible food systems, protecting biocultural diversity, animal welfare, climate, and the environment

- Gutes Essen macht Schule (Hamburg): Initiative for a food system transformation in Hamburg and healthy nutrition in schools and other public institutions

NGOs working on food security, emergency hunger relief, and/or raising awareness

- Agrarkoordination – Forum for international agricultural policy

- FIAN – fighting hunger through human rights

- Welthungerhilfe – for a world without hunger

- Oxfam – for a world without poverty

- Foodwatch – the food rescuers